Maybe you’ve heard this term when configuring your graphics settings, or maybe it’s something that’s happening to your digital signals. But what is Aliasing and why is it so bad? I’ll talk about aliasing in terms of digital signal processing, but this information is also applicable in other areas.

Digital Signals

In terms of music, a signal is a waveform; just changes in pressure over time. In real life, a wave is an analog signal, which means that the signal changes smoothly.

Consider the above signal, the voltage varies from 0.1V to 3.3V. There are infinitely many numbers between 3.3V and 0.1V, so our analog signal will sweep through an infinite amount of numbers.

In the world of computers this is a fundamental problem. Computers can only hold a finite amount of information, so representing an analog signal perfectly is impossible with digital computers. This is where digital signals come in. Digital signals are not smooth, instead they take only a finite selection of values.

The second property of a digital signal is that it will change value in set time intervales, much like the frame-rate of a camera. With these two limitations, computers can handle digital signals.

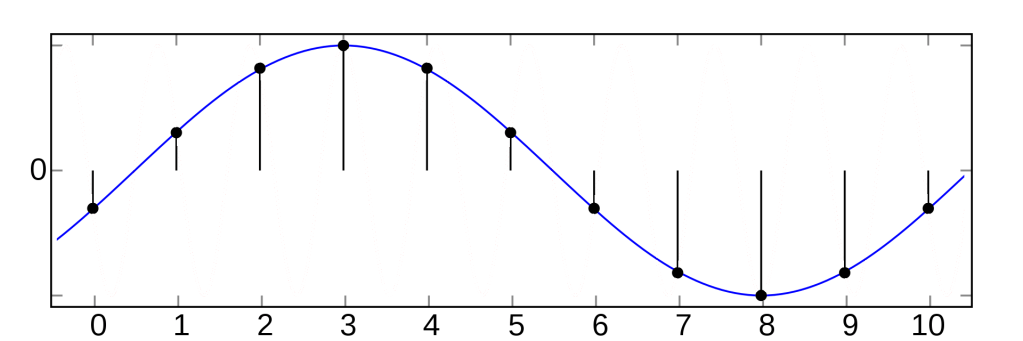

We can try to approximate an analog signal with a digital signal. Essentially the idea is to take snapshots of the analog signal, called samples. It’s the same idea as a camera taking many still images to re-create smooth motion. The result looks like this:

You’ll notice that the red line has to travel on a grid. This is because it can only be on a finite number of levels, and changes in fixed time intervals.

Right now, it seems that digital signals look a bit rubbish. How could you posssibly get warm, lush, beautiful, pad sounds from these square looking things? Time to introduce some terminology:

Sample rate: The number of samples taken per second.

Bit depth: The number of bits used to represent each sample. This can be thought of as the number of levels the signal can be at.[1]

Looking at the picture above, increasing the sample rate will increase the number of vertical dotted lines and increasing the bit-depth means more horizontal lines. This means that if we increase both of these, the grid will become smaller and we can closely follow the analog signal. But, increasing these comes at the cost of larger file sizes, so we need to think carefully about how much of each is “good enough”, instead of going berserk.

I’ll gloss over digital-to-audio conversion here, but essentially the conversion involves connecting the dots created by the digital signal.

Aliasing

Now we have established how an analog signal is converted to a digital signal, let’s talk about aliasing. The easiest way to understand it is to just think about an example. Say we want to convert this red analog signal to digital:

Remember that only the samples are stored in the computer, since the digital signal can’t be stored in a computer. So after we have sampled this, this is what the computer sees:

Now the problem should be clear, the sample doesn’t look anything like the original wave! When it comes time to convert this back to the analog signal that the speakers will use, it will look something like this:

The red wave and the blue waves are called aliases, hence the term aliasing. In fact, any analog wave will have an infinite number of aliases. In some sense, the aliasing effect occurs at the stage of digital-to-analog conversion(DAC). A strange DAC might have reproduced the red wave correctly, but this type of DAC would fail in most applications.

So what is the cause of this? Well the reason is actually quite similar to the wagon wheel effect, which can be seen to the right. Essentially, the frequency of the signal is too high when compared to the sample-rate.

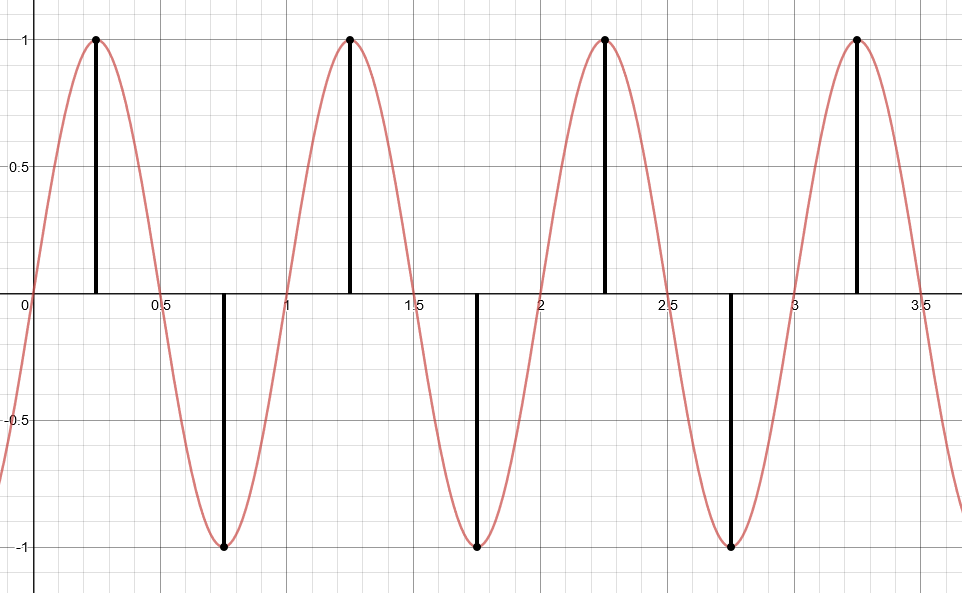

What is the highest frequency we can achieve with a digital signal? Well if we have 1 sample at the maximum, then the next at the minimum and repeat this, we have a signal that has the frequency of half the sample rate:

In fact, Harry Nyquist proved that a signal can be sampled and perfectly reconstructed from its samples if the waveform is sampled over twice as fast as it’s highest frequency component[2]. So, as long as we sample twice as fast at the highest frequency component of the analog signal, we should be alright. What do I mean by “frequency component”? Without going into too much detail, we’re talking about the frequency spectrum of the analog signal:

This frequency spectrum includer the overtones of the signal, so bear in mind that even a 440Hz saw tooth wave has infinitely many overtones. So your saw-tooth wave won’t ever be perfectly re-constructed. Or will it? Because bear in mind that human hearing only goes up to 22kHz, so we won’t be able to hear overtones about that frequency anyway. Using Nyquist’s theorem, we sample at twice that rate, at 44kHz so shouldn’t be able to tell the difference. That’s why an mp3 has a sample rate of 44kHz.

Anti-aliasing

So you might think that setting the sample-rate to 44kHz will solve all our problems and we can go home now. No! Aliasing can still be a problem at even when sampling at 44kHz. Think about the red wave example earlier. We had a high frequency red wave, with a lower frequency blue wave as it’s alias. So let’s say we had an analog signal with frequencies above 25kHz. These high frequencies would normally be inaudible but, when we sample them they produce a lower frequency alias that we can hear. Frequencies that we can’t normally hear will interfere with the audio output.

This is where the anti-aliasing filter comes in, it’s a low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency at half our sampling rate[3]. This will ensure that any frequencies where aliasing could appear are removed. At a sample rate of 44kHz, this anti-aliasing filter will only remove inaudible frequencies, so our analog signal will be almost perfectly re-created. The only problem is that the digital signal has fixed levels, due to the bit-depth. So the analog signal won’t be perfectly re-created.

Conclusion

- An analog signal can’t be represented in a digital world. So digital signals must approximate them

- Aliasing occurs when the signal being sampled has frequencies above half the sampling frequency

- You can use a low-pass filter to avoid aliasing

Sources and further reading

- Proakis, John G.; Manolakis, Dimitris G. (2007) Digital Signal Processing

- Nyquist sampling theorem

- Aliasing and Anti-Aliasing Filters