The question

Consider the following melodies:

- Melody 1: C-E-G

- Melody 2: B-C-C#

“Melody 1” could be a melody in C Major, or maybe it could be in G Major. On the other hand, “Melody 2” is chromatic. So there isn’t any key that those notes all belong to. So the question is, can we categorise all non-diatonic melodies?

Breaking down the question

The words diatonic and chromatic are being abused here. By “chromatic” I mean that it doesn’t fit into any major scale, and diatonic is the opposite here. Anyway…

At first glance this may seem like a tall order; there are infinitely many melodies. For simplicity, I’ll say that any melody with any chromatic section is considered to be a “chromatic melody”. But also consider that, since the major scale repeats every octave, only melodies of length less than or equal to 12 have to be considered. Why? Well, the order of the melody doesn’t matter when thinking about if it’s chromatic or not, so the repeated notes can be ignored.

So let’s see… there are 12^12 = 8.91 * 10^12 possibilities. The good news is that it’s finite, but sadly so is my life. This would take too damn long to brute force. So how can we narrow this down? The first thing to think about is that repeated notes can be removed from a melody. What we’re really thinking about are subsets of the 12 notes. But more than that, we can assume the first note is, say, C. This reduces us down to only 2^11 = 2048 things to think about, because we know we have C, and now we either do or don’t add the other 11 notes.

So really we’re just thinking about which notes are in our melody, not the order. Let’s take an example of why this thinking works. Going back to “Melody 2”, think about the following melodies:

- G-B-C-C#-F-D

- This one is chromatic because it contains the chromatic sub-melody B-C-C#.

- C-B-C#

- So is this one, but it’s in a different order.

- D-E-F-G-E-C-D-B-C#

- This is also chromatic because is contains the sub-melody that’s in a different order

The point I’m trying to make is that all 3 of the above melodies are known to be chromatic because they have the notes C, B, and C#.

Now we’ve simplified the melodies, let’s talk about scales. For the purposes of this question, the functions of each note don’t matter, so we can forget about all the modes. Also it doesn’t really make sense to say that a melody is intrinsically chromatic, really it’s chromatic with respect to some scale. To illustrate my point, think about how, in the major scale, every minor third is proceeded by a whole step. Now think about B-D-Eb. It won’t fit into any major key, but it does fit in to with C melodic minor.

To recap:

- We don’t need to think about melodies, only which notes are in the melody

- Forget about modes for now

- A melody is only really chromatic in the context of which scale you’re talking about.

So what?

I’ll skip to the results now. Implementing this brute force search in C# was pretty pedestrian.

The aim of this post is to find out “rules” that we can apply to a melody to check if it’s chromatic with respect to a given key. Examples of rules that make a melody chromatic:

- Two consecutive half-steps

- A minor third followed by a halfstep

- Any minor chord followed by the same chord but major(e.g. Em followed by E)

Notice the third rule is just a sub-category of the second, since you’ll get a minor third followed by a major third, which is a half-step above. So I’ve filtered out any rules that are encompassed by others.

Major scales

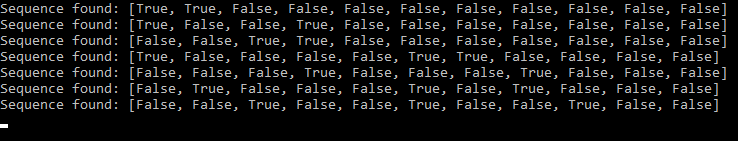

First up, the major scales and all their modes. The results are in:

What does the mean though? Well, starting from C, we have a true if that note is in the melody and a false if it’s not. So the first sequence is just saying C-C#-D. Of course, it doesn’t have to start from C, it could start from any note. So really this translates into the rule saying that 2 consecutive half-steps is chromatic. So translating all of these into English, we have the 7 types of chromatic types of melodies/chords (for major keys):

- Two consecutive half-steps

- E.g. D-D#-E

- A half-step followed by a minor third

- E.g. E-F-G#

- A minor third followed by a half-step

- E.g. C-D#-E

- A half-step, followed by a perfect fourth, followed by another half-step

- E.g. D-D#-G#-A

- Two consecutive major thirds

- E.g. F-A-D#

- A whole-step followed by a major third, followed by another whole-step

- E.g. C-D-F#-G#

- Three consecutive minor thirds

- E.g. F-Ab-B-D

Note that I’m constructing these from a base note upwards. As established earlier, the above types can be re-ordered and put into larger melodies.

Pentatonic scale

Since the pentatonic scale is a sub-set of the major scale so you might expect this to have more types of chromatic melodies. But actually it only has 3 types:

- One half-step

- One diminished fifth

- Two consecutive major thirds

Melodic Minor

- Two consecutive half-steps

- Half-step followed by a minor third, followed by another half-step

- Half-step followed by a major third, followed by another half-step

- Half-step followed by two minor thirds

- Minor third followed by a half-step followed by another minor third

- A half-step, followed by a perfect fourth, followed by another half-step

- Two consecutive minor thirds followed by a half-step

- A half-step, followed by a major third, followed by a minor third

- Three consecutive minor thirds

- Five Consecutive whole-steps

Ok, ok, that’s enough…

Why tho?

The above rules seem quite random, and you may ask if this is useless knowledge. Well, maybe…

For me it’s more of a mathematical curiosity, and I was hoping to find some patterns. If you have found this useful please e-mail me how you used it, because I can’t find any substantial use of these facts.

Even better if…

There’s still more work to be done here. For example, I know that if I play a major third the melody is contained in some major key, but how many? So far I’ve only looked at the situations where you end up in none of the major keys. But I think that’s a project for another day.

And what about Super Ultra Hyper Mega Meta Scales?